By Arthur Dominic J. Villasanta , | April 25, 2017

Scientists have developed a way to trigger a chemical reaction in a synthetic material called metal-organic frameworks (MOF) that breaks down carbon dioxide into harmless organic materials.

A team from the University of Central Florida (UCF) claims to have found a way to trigger photosynthesis in a synthetic material that transforms greenhouse gases into clean air while also producing energy.

The process has great potential for creating a technology that could significantly reduce greenhouse gases linked to climate change, while also creating a clean way to produce energy, alleges Assistant Professor Fernando Uribe-Romo at UCF, the team leader.

Like Us on Facebook

"This work is a breakthrough," said Uribe-Romo.

"Tailoring materials that will absorb a specific color of light is very difficult from the scientific point of view, but from the societal point of view we are contributing to the development of a technology that can help reduce greenhouse gases."

The findings of his research are published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A.

Uribe-Romo and his team of students created a way to trigger a chemical reaction in a synthetic material called metal-organic frameworks (MOF) that breaks down carbon dioxide into harmless organic materials.

Think of it as an artificial photosynthesis process similar to the way plants convert carbon dioxide (CO2) and sunlight into food. But instead of producing food, Uribe-Romo's method produces solar fuel.

It's something scientists around the world have been pursuing for years, but the challenge is finding a way for visible light to trigger the chemical transformation.

Ultraviolet (UV) rays have enough energy to allow the reaction in common materials such as titanium dioxide, but UVs make up only about four percent of the light Earth receives from the sun.

The visible range -- the violet to red wavelengths -- represent the majority of the sun's rays, but there are few materials that pick up these light colors to create the chemical reaction that transforms CO2 into fuel.

Researchers have tried it with a variety of materials, but the ones that can absorb visible light tend to be rare and expensive materials such as platinum, rhenium and iridium that make the process cost-prohibitive.

Uribe-Romo used titanium, a common nontoxic metal, and added organic molecules that act as light-harvesting antennae to see if that configuration would work. The light harvesting antenna molecules called N-alkyl-2-aminoterephthalates can be designed to absorb specific colors of light when incorporated in the MOF. In this case he synchronized it for the color blue.

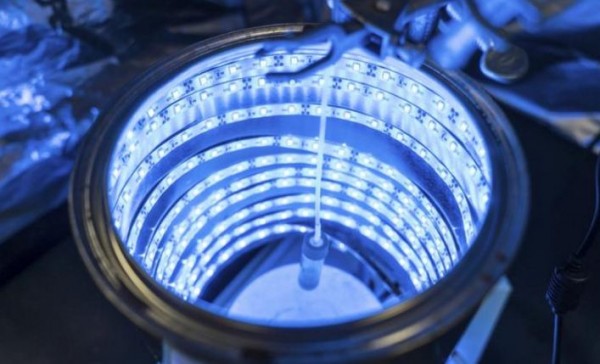

His team assembled a blue LED photoreactor to test the hypothesis. Measured amounts of carbon dioxide were slowly fed into the photoreactor -- a glowing blue cylinder that looks like a tanning bed -- to see if the reaction would occur.

The glowing blue light came from strips of LED lights inside the chamber of the cylinder and mimics the sun's blue wavelength.

It worked, and the chemical reaction transformed the CO2 into two reduced forms of carbon, formate and formamides (two kinds of solar fuel) and, in the process, cleaned the air.

"The goal is to continue to fine-tune the approach so we can create greater amounts of reduced carbon so it is more efficient," said Uribe-Romo.

The idea would be to set up stations that capture large amounts of CO2, like next to a power plant. The gas will be sucked into the station; go through the process and recycle the greenhouse gases while producing energy that will be transferred to the power plant.

To see an explanation see this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cdTuwe2SruA&feature=youtu.be

-

Use of Coronavirus Pandemic Drones Raises Privacy Concerns: Drones Spread Fear, Local Officials Say

-

Coronavirus Hampers The Delivery Of Lockheed Martin F-35 Stealth Fighters For 2020

-

Instagram Speeds Up Plans to Add Account Memorialization Feature Due to COVID-19 Deaths

-

NASA: Perseverance Plans to Bring 'Mars Rock' to Earth in 2031

-

600 Dead And 3,000 In The Hospital as Iranians Believed Drinking High-Concentrations of Alcohol Can Cure The Coronavirus

-

600 Dead And 3,000 In The Hospital as Iranians Believed Drinking High-Concentrations of Alcohol Can Cure The Coronavirus

-

COVID-19: Doctors, Nurses Use Virtual Reality to Learn New Skills in Treating Coronavirus Patients